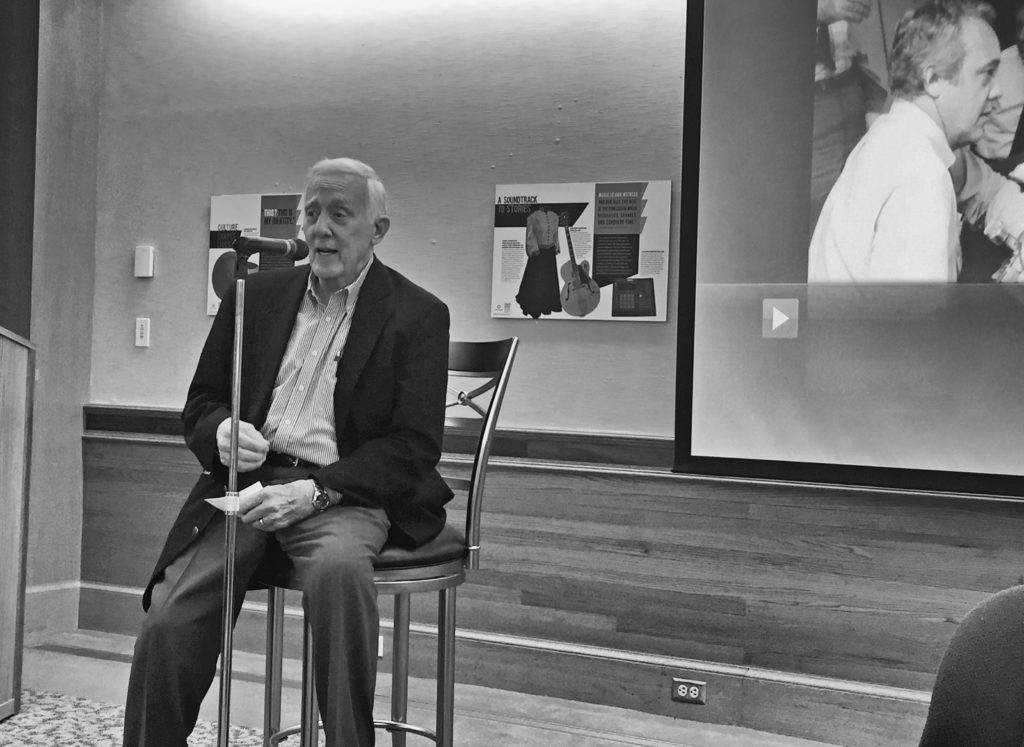

Editor’s note: Steve Bell spoke to the noon Muncie Rotary Club on Wednesday and presented a :30 minute rough cut of a documentary covering his life and experiences as a television journalist. The documentary is being produced by Bob Mugge and his wife Diana Zelman. Lisa Renze-Rhodes, Director of Media Strategy at Ball State University interviewed Steve about his life and experiences as a television journalist. Her story is below.

Muncie, IN—Every push and pull of his bike pedals meant adventure for Steve Bell and his grammar school pals as the trio cruised past familiar landmarks in their comfortable hometown. Past the Rivola Theater on High Avenue, with its marquee hawking “Sergeant York” or Boris Karloff’s “Isle of the Dead,” over the tracks next to the Rock Island Railroad depot and around the bandstand in the city square, the boys found freedom regulated only by an occasional dropped chain and the piercing whistles that signaled the end of carefree days.

“We all lived near each other, and our mothers each had a different whistle,” Bell explained during a recent chat inside his Muncie home. “When you heard your whistle, you were expected home.”

Such was life in Oskaloosa, Iowa, in the 1940s. Victory gardens bloomed, Bell got up before dawn to fold the Daily Herald into compact squares he would then hurl onto front porches, and teenagers left town to fight battles that raged half a world away.

He could never have imagined that he would one day be the man returning home from war-torn nations, not as soldier or sailor, but as a foreign correspondent for ABC News. As the longtime journalist and first Edmund F. and Virginia B. Ball Endowed Chair in Telecommunications at Ball State prepares, with friends and former colleagues, to celebrate the 40th anniversary of “Good Morning America,” Bell took time to reflect on a career that brought him to the brink and back.

“For two kids from Iowa, we were so blessed,” Bell said about himself and his wife, Joyce, his high school sweetheart and forever partner. “You don’t think about it at the time it’s all happening. I’ve always thought journalism was a calling, because you’re sustained in part by the belief that you are one small piece of a very large, important pursuit. You had a role to play. If Joyce had not been the kind of person who was willing to have that life, too, it would not have worked out.”

Bell’s career reads like a Time Life series. As a green reporter just starting out, he was on the scene for Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev’s visit to his home state. Just four years later, after making the transition from radio to TV, Bell was sent to Dallas after word came across the wires to his bosses at WOW in Omaha, Nebraska, that President John F. Kennedy had been shot. He was in Newark, New Jersey, at the beginning of what was known as the “long hot summer.” It was 1967 and as riots broke out around the city, Bell, crouched behind trash cans and trashed cars, captured the sounds of the gunfire exchange between protestors and police.

Next came orders to cover the aftermath of the assassination of the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. It was there in Memphis, Tennessee, that the man who had once imagined himself as a high school football coach and teacher found he was exactly where he was supposed to be.

After securing a rental car and gathering information from city police, Bell traveled to the Lorraine Motel. “I was able to walk up the stairs and stand on the balcony where the shooting took place.”

Blood remained on the concrete. After crossing the parking lot, Bell wound his way through a nearby boarding house to peer at the motel from the vantage point of the bathroom window, where James Earl Ray’s fatal shot was fired.

“To stand there, and to know I’d done the same thing when John F. Kennedy was killed, it was a powerful moment. I just stood and thought about the historical context.”

But history or no, Bell’s deadline neared. So he drove to the funeral home where King’s body had been taken. With no one at the door to greet or question him, and with no other reporters in sight, Bell made his way into the room where King’s closest advisors, staff and a few community members stood, circling the casket.

“Suddenly, people put their arms around each other and they began to sing, ‘We Shall Overcome,’” Bell said. He immediately got out his recorder to capture the ambient sound and to tape his report at the scene. “The problem was that I was so choked up, I couldn’t get the words out.”

Several attempts later, Bell was able to finish the piece and had a story he could send back to his network. But he’s never forgotten that place in time.

“It’s certainly one of the moments that was most emotional, and in its own way, most important, of anything I did later.”

Later came very soon.

‘Something’s happened. Something terrible has happened.’

Two months later, Bell was on the road covering Robert Kennedy’s presidential campaign. During a stop in Oregon, Bell learned that his second daughter, Hillary, had been born. After a quick flight home to meet his baby girl and check on Joyce, Bell, at his wife’s insistence, was back on the road, picking up the campaign in Los Angeles.

“I’ve always thought journalism was a calling, because you’re sustained in part by the belief that you are one small piece of a very large, important pursuit.” — Steve Bell, retired professor of telecommunications

Reporters and photographers crammed onto the dais at the Ambassador Hotel along with Kennedy’s family, staff and other supporters. Footage of the night’s speech shows Bell next to the podium, leaning toward the senator to capture the sound on a hand-held recorder. The crowd and the candidate were all in good spirits that night, and Kennedy, Bell said, was taking his time in the moment before eventually exiting the stage.

Minutes later, as Bell was working to follow Kennedy and his entourage, two men came rushing back toward the crowd, carrying a bleeding woman. Bell pushed forward.

“Something’s happened. Something terrible has happened… There’s blood all over the floor,” Bell said in the tape made that night, as he came onto the full scene. “Senator Kennedy has been shot.”

As police flooded the hallway, Bell jumped on a serving cart to get above the melee, where he continued to record events. It seemed almost unbelievable that another leader of the times had been taken. He was a witness again.

“It’s just incredible to think about even today,” he said.

The approach of a new decade brought the chance of a lifetime, Bell says now, as he and his family left the States to begin life in Hong Kong. Bell was set to begin a stint as a war correspondent for ABC, covering the events in Vietnam, Laos and Cambodia.

Even all he’d seen couldn’t have prepared him for the road ahead.

The most important story

Unlike in Vietnam, where journalists traveled with American troops, news teams in Cambodia hired private cars and drivers to take them into hot zones. Checkpoints provided tense moments for reporters, photographers and sound men traveling through contested areas. Boundaries changed rapidly, and one morning Bell and his crew slipped past a checkpoint guarded by a single, teenage soldier.

As the crew came up Highway 1, Bell said an odd scene began taking shape. Stretched across the ground were men, women and children who appeared to be lying out in the hot sun.

“But we got closer and you knew, you could see, they were all dead,” Bell said. A total of 97 ethnic Vietnamese villagers who lived in Cambodia had been massacred.

“It was the worst thing you could imagine, and certainly beyond anything that any of us had seen.”

After doing what they could for the few survivors, Bell and his crew did the only other thing they knew how to do — record the scene.

“We were able to get that film shot and get it back to Phnom Penh (Cambodia’s capital),” Bell said. After literally taping all the film canisters to the sound-man’s body to get past censors and putting him on a flight to Bangkok, Bell, deeply disturbed, returned to his hotel room in the city. Though the crew had successfully gotten the live sound, raw footage and Bell’s report out of the country, it would still be nearly 24 hours before the world would know what happened.

As Bell debated what action to take, he got word that a call from then-Hong Kong bureau chief Ted Koppel had come in. All international calls had to be taken at the city’s official telephone and telegraph offices, where censors were standing by. Bell told the censor that he didn’t have a story script to be reviewed, because he was receiving instruction on his next assignment. But the call gave Bell an opportunity.

“Ted got on the phone, and he did have information from New York to tell me,” Bell said. But before the call ended, Koppel tossed Bell a softball.

“How are things going?” Koppel asked.

“Not bad,” Bell replied. “We found some people who went to a party last night … I counted 97 partygoers who had such a good time, they’ll never go to another party.”

Koppel immediately took note. The coded exchange continued, and Bell was able to relay to Koppel just what had occurred in the village, getting the story on the radio 12 hours before the TV version was ready for air. In the two weeks after Bell and his crew reported the first massacre, two more massacres were found and reported by Bell and other journalists. In just over three weeks, an estimated 1,000 ethnic Vietnamese had been killed.

The public outcry from the stories Bell and the other journalists reported created a groundswell of pressure on the Cambodian government to step in and put a stop to the killings.

“In my whole career, that was the hardest, and the most important story, I ever did.”

Saying good morning

Three years later, while serving as chief Asia correspondent, Bell got an assignment returning him to the States to cover the Watergate scandal as a White House correspondent. So the family headed back to D.C. and Bell again found himself recording history as it was happening. His coverage of the resignation of President Richard Nixon, coupled with the decades of news experience he had, positioned him for the next challenge in his career.

Bell on ‘Good Morning America’

The retired telecommunications professor discusses some of his most memorable moments while working on the TV show. Read more.

Soon 1974 turned to 1975, and Bell answered another call — this one to the anchor desk for a new morning news show that was being developed by ABC to compete with NBC’s “Today.”

“When I was offered the job, a lot of people asked why I would want to leave the White House press corps for a program that probably wouldn’t last a year,” Bell said. “But I saw it as an opportunity.”

As the show some said wouldn’t last prepares to celebrate its 40th anniversary, Bell said the early days of “Good Morning America” were about learning and doing, and making lifelong friends, including GMA’s first host.

“David Hartman and I developed a great relationship,” Bell said. “Audience research was key. It emphasized that we were being invited into people’s homes at a busy and private time of day.

“People were getting dressed, having breakfast, getting the kids off to school and getting themselves to work, either inside or outside the home. What they wanted was a ‘family’ atmosphere with concise news and weather summaries, and interesting interviews and features that would help them prepare for the day.”

From his network news-desk, Bell, along with his GMA colleagues, told the world about critical stories of the time, including the 1980 assassination of John Lennon. “The question of course that hasn’t been answered yet this morning is why former Beatle John Lennon was shot to death last night,” Bell said in his report.

Weeks later, Bell and the GMA crew again alerted the world to historic events — this time it was the release of the 52 Americans who had been held as hostages at the U.S. Embassy in Iran for 444 days.

“Because of the time differences, daytime events in the Middle East and Europe were often happening during our air time,” Bell said. “As a result, I had the opportunity to anchor special coverage of many major news events.”

Bell spent nearly a dozen years with GMA and co-anchoring ABC “World News This Morning.”

Building a future

Bell returned briefly to local TV news in the late 1980s, but after five years decided it was time to do what he had planned to do when he first went to college.

“The offer to be the first Ball Endowed Chair in Telecommunications, and to teach broadcast news, was perfect. … From the very moment I arrived, I was so impressed with Ball State.”— Steve Bell, retired professor of telecommunications

Bell said a good education prepares good reporters, and though he’s no longer in the classroom, his belief is as strong as ever.

“There’s never been more need for good journalists,” Bell said. “The bad news is there are fewer and fewer large companies willing to pay for it. But that’s where reporters can and should take advantage of all the new technologies available — to create forums where important news can be shared. Those technologies are changing the role of journalists.”

As more people “self-subscribe” to only beliefs they currently hold, Bell said, a wider, full-picture view of the world is more critical than ever.

“Objectivity may be laughed at by some, and it may be impossible, but it’s the best goal going,” he said, showing the educator side of himself that’s never gone away.

“I still believe that striving for objectivity is the best model. Journalism is still an honorable profession. I’m blessed to have had the opportunity to follow my calling.”