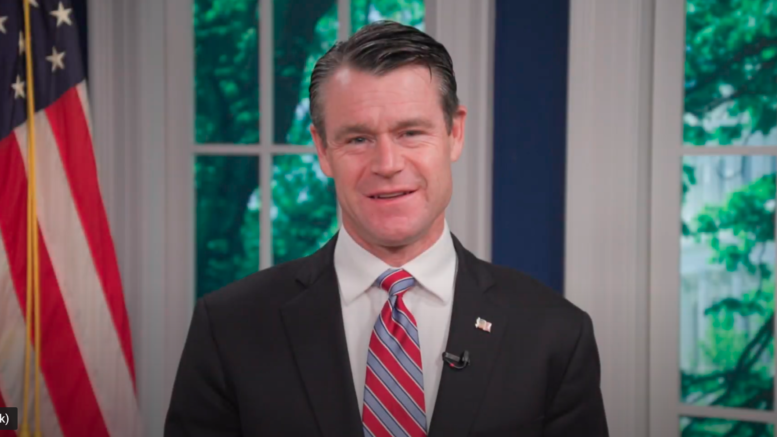

By U.S. Senator from Indiana Todd Young—

INDIANAPOLIS, Ind.—In the town of Hartsville, in Bartholomew County, not more than 60 miles south of here, there is a small red headstone in a Baptist cemetery. It reads simply: B.W. Mitchell 1816-1868. Below that, it mentions the 27th Indiana volunteer infantry in letters so small they strain the eye.

Corporal Barton Warren Mitchell was a 45 year old railroad worker from Putnam County who joined the Union Army at the onset of the Civil War. In his life Corporal Mitchell was little known. He remains so today. No biographers have painstakingly retraced his life. His heroic deeds on the battlefield are not regularly recounted. Other than a $13 a month salary as a corporal, his government gave him no decorations or awards. There is no monument and memorial to him, only a small marker on State Road 46.

By simply doing his duty, though, this Hoosier soldier changed the course of history.

You see, in September 1862 Corporal Mitchell discovered an envelope laying in a field near Frederick, Maryland. Inside were three cigars, wrapped in a piece of paper. On that paper were written Robert E. Lee’s plans to invade the North.

Corporal Mitchell carried the piece of paper to his captain…who took it to his colonel…who jumped on his horse and rushed it off to headquarters. Once there the document — Special Orders No. 191, the Lost Order — landed in the hands of George B. McClellan, commanding general of the Union army.

The rebels’ plans clear, he moved his army west and attacked Lee, culminating in the battle of Antietam, a bloody draw but a tactical victory – one that encouraged Abraham Lincoln to issue the Emancipation Proclamation, transforming the Union war effort into a moral cause to end slavery, rescuing our Union.

All because a rank and file soldier did his duty.

For over two centuries America’s soldiers, the men and women who make up freedom’s army, have changed the course of history by doing their duty.

They defy categorization: they were farmers and shopkeepers, former slaves and newly arrived immigrants…they are black and white, rich and poor, son and daughter, father and mother, from Bartholomew County and Brooklyn alike.

From Lexington and Concord to Abbey Gate they have left home, left behind loved ones, not to seek glory or win treasure, but to defend the uniquely American idea that all men and women are created equal and capable of self-government.

Without their blood and sacrifice, without all the Corporal Mitchells, the common soldiers whose names we don’t know, whose brave deeds, big and small, are little known, our institutions, our government, our communities, our way of life, instantly vanish.

Living and dead, they are as Lincoln once said, the pillars in the temple of liberty.

On Veterans Day, we honor and thank all Americans who have shouldered the terrible cost of war.

It falls to us and future generations to care for our veterans and those they leave behind. But I believe we have to do more.

If our veterans can risk and so often forfeit their lives for our freedoms, we can remember to see our fellow citizens as countrymen and friends. We can remind ourselves how precious and hard earned those freedoms are and never seek to deny another American of them. And we can resolve that no matter how great our passions, the Union preserved by veterans like Corporal Mitchell will forever stand and never break.

It may not be easy, but I believe by comparison, it’s not a great sacrifice.

Corporal Mitchell, by the way, was injured during the battle of Antietam; he spent eight months in a hospital, returned to his company and mustered out of the army in Indianapolis in 1864. His injuries never fully healed. He quietly returned to civilian life, moved to Hartsville and operated a sawmill. Before he died in 1868 he wrote to the federal government asking about recognition for his role in finding the Lost Order, with no success.

After his death, Corporal Mitchell’s son continued those efforts with similar results. A letter to his father’s old colonel was answered with a promise though:

“The memory of your father and his gallant services in my old regiment ever be duly appreciated by me. Anything I can do for his widow and family will be cheerfully done.”

Let the memory of the gallant services of our veterans ever be duly appreciated.

And anything we can do, not just to help them and their families, but to cherish what they have fought for, let us do it cheerfully.

They have given so much. Let us never grow ungrateful.